Summary of the history of the Polish comic

Summary of the history of the Polish comic.

Wojciech Birek, Piotr Machłajewski

In the second half of the 19th century, picture stories appeared in weekly magazines and illustrated magazines published in Poland. They took various forms, from the classic arrangement of clearly separated drawings with verbal commentaries to experiments with graphic styles and compositional arrangement of pictures in the form of a board. They were published in such magazines as Tygodnik Illustrowany (Weekly Illustrated) (1859-1939), in which Franciszek Kostrzewski developed his rich creativity, Kuryer Świąteczny (1864-1918), Kłosy (spikes) (1865-1890), Wędrowiec (Wanderer)(1863-1906) and "Mucha" (Fly) (1868-1939). At that time several generations of talented artists honed their craft in the illustrated press. Apart from Kostrzewski or brothers Henryk and Ksawery Pillati (1832-1894, 1843-1902) these included Stanisław Lenc (1861-1920), Stefan Mucharski (1859-1928) and Kazimierz Grus (1885-1955). but also well-known painters, graphic artists and illustrators, such as Juliusz Kossak (1824-1899), Wojciech Gerson (1831-1901) and Artur Grottger (1837-1867). Those stories were dominated by moral themes with touches of social criticism and strong satirical overtones.

In 1918 Poland regained its independence. The first important Polish comic book is considered to be the humorous-patriotic series called Ogniem i mieczem, czyli przygody Szalonego Grzesia (With a fire and a sword, adventures of crazy Gregory) which tells the adventures of a brave soldier fighting Poland's enemies, including the Bolsheviks. The series was published in 1919 in the Lvov satirical weekly Szczutek, and its authors were journalist Stanisław Wasylewski (1885-1953) and cartoonist Kamil Mackiewicz (1886-1931).

In the interwar period, Poland dominated traditional picture stories with captions under the illustrations; however, there were also modern comic strips with balloons. There were willingly published Reprints or alterations of well-known American comic books with adventures of such heroes as Betty Boop, Blondie, Flash Gordon, Mutt & Jeff, Popeye, Prince Valiant or Superman. Some foreign comic books were adapted to Polish reality, and their heroes were "naturalized", given Polish names and entrusted to Polish artists to create their new adventures. This happened, for example, with the Swedish Adamson, "appearing" in Poland under the name Agapit Krupka, or the Danish comedians Pat and Patachon, whose Polish adventures were drawn by Wacław Drozdowski (1895-1951) (after the war their names were changed to Wicek and Wacek).

The longest of the Polish stories was Przygody Bezrobotnego Fronck (The Adventures of the Unemployed Fronck), drawn by Franciszek Struzik (1902-1944) and published every day for seven years in episodes in the Silesian afternoon magazine Siedem Groszy (Seven Pennies.) The most productive pre-war creator of picture stories was Stanisław Dobrzyński from Łódź (1897-1949) - author of approximately twenty series, including the adventures of Jaś Klepka, Lopek and Winnie the Detective ( Jasia Klepka, Lopek, Kubuś detektyw). Jerzy Nowicki specialized in drawing stories with characters borrowed from foreign series: Flip and Flap, Tarzan, Charlie Chaplin.Aleksander Świdwiński drew a "futuristic" series entitled Warszawa w roku 2025 (Warsaw in 2025) based on texts by Benedykt Herz. The picture series were published mainly in the local and afternoon press. Aleksander Świdwiński drew a "futuristic" series entitled Warszawa w roku 2025 (Warsaw in 2025) based on texts by Benedykt Herz. The picture series were published mainly in the local and afternoon press.

Among the most important interwar picture story magazines are Grześ (Gregory) (1919-1920), Świat Przygód (The World of adventures) (1935-1939), Karuzela (Carousel) (1936-1939), Wędrowiec (Wanderer) (1937-1939), Tarzan - tygodnik przygód i powieści egzotycznych (Tarzan - weekly of adventures and exotic novels) (1937) oraz tygodnik z komiksami Walta Disneya Gazetka Miki (Miki’s Little journal) (1937-1939), equivalent to the French Le journal de Mickey. In contrast to press publications, books with comic books appeared in Poland sporadically. In 1932, a picture story was created, which permanently entered the Polish literary canon and is still reissued. It was 120 przygód Koziołka Matołka (120 Adventures of Koziołek Matołek) written by a well-known writer Kornel Makuszyński (1884-1953) and a cartoonist Marian Walentynowicz (1896-1967). Clear, colorful drawings accompanied by funny rhyming comments told the story of a "humanized" goat wandering around the world in search of the mythical Pacanów - a place where, according to a well-known Polish saying, goats are shoeled. The Adventures of Matołek has been published in four booklets, and its authors have also created several other popular drawn tales with a similar formula.

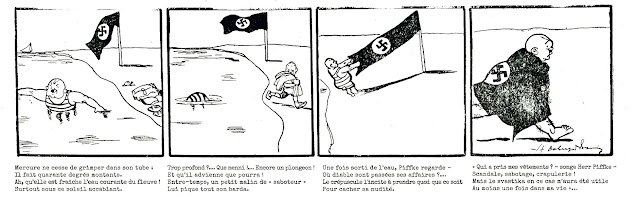

The outbreak of World War II and the years of German occupation put an end to the independent Polish press. It was replaced by publications supervised by the occupation authorities, with a clearly propagandistic message. Cooperation with them was treated as collaboration. Comics were rarely published in those periodicals. The activity of Polish artists moved to emigration. Drawn tales appeared, for example, in the United States - in the magazine Odsiecz - Polska Walcząca w Ameryce (Succour - Poland fighting in America) (1941-42), Walenty Pompka began his life in exile, created by the cartoonist Marian Walentynowicz and Ryszard Kiersnowski (pseud. Ryszard Pobóg). In the Middle East, during the II Polish Corps stationing there, the magazine Junak was published, with a comic strip entitled Przygody Hilarego Pały (The Adventures of Hilary Pala). In 1943 a supplement to Dziennik Żołnierza APW (The Journal of APW Soldier) entertained readers in uniform with the adventures of Kuba Łazik by Wlodzimierz Kowańko and Jerzy Laskowski. After World War II there was a difficult period for comics in Poland. The communist authorities took control of the publishing market. In the new realities, comics, associated with Western culture, became a phenomenon worthy of condemnation and criticism. Contacts with foreign publishers were severed ( except publications by, for example, French communists) and the focus was placed on publishing the work of local authors, often imposing on them propaganda tasks: comic books glorified the virtues of the socialist system and criticized capitalism.

The comics were primarily published in the press. A sequel was also published in Świata Przygód (The World of Adventures) It was published as Nowy Świat Przygód (New World of Adventures) (1946-1947), and later Świat Przygód (World of Adventure) (1947-1949), which was later merged with the scouting biweekly Na Tropie (On The Track). As a result of this merger, Świat Młodych (The World of Youth) (1949-1993). In the years 1957-1958, due to political thaw, 98 issues of the weekly for youth Przygoda (Adventure) were published. The magazine was modelled on the French communist magazine Vaillant, which had been printed in Poland. Among the most important authors publishing in the press at the time were: Zbigniew Lengren (1919-2003), author of a series of silent strips entitled Prof. Filutek. Janusz Christa (1934-2008), who was associated with the Gdansk afternoon magazine Wieczór Wybrzeża (Evening of the Coast). Since 1958, he published a series of strips about the adventures of Kajtek-Majtek, then Kajtek and Kok and Kajek and Kokosz. Jerzy Wróblewski (1941-1991), long time collaborator of Bydgoszcz's Dziennik Wieczorny (Evening Journal). Henryk Jerzy Chmielewski - Papcio Chmiel (Hop Daddy (1923-2021), best known for his Tytus, Romek and A'Tomek series published in Świat Młodych (The World of Youth).

In the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, a form of stand-alone comic book publications called kolorowe zeszyty (colorful notebooks) flourished in Poland, as the communist authorities tried to use them to warm up the image of the militia and the army. The longest published series was a detective series about the adventures of a Citizen's Militia officer, titled Kapitan Żbik(Captain Wildcat). Captain Wildcat was published Between 1968 and 1982 in 53 episodes with the total circulation of over 11 million copies. The series was drawn by i.a. Grzegorz Rosiński (1941), Bogusław Polch (1941-2020) and Jerzy Wróblewski. In those days, comic books that were related to well-known and well-loved TV series were popular. Prominent series were: Podziemny front (Underground Front) (1969-1972) with drawings by Mieczysław Wiśniewski (1925-2006) and Jerzy Wróblewski. Other series included: Przygody pancernych i psa Szarika (Adventures of armor troopers and dog greyer) (1970-1971) with drawings by Szymon Kobyliński (1927-2002), Kapitan Kloss (Capitan Kloss) (1971-1973) with drawings by Mieczysław Wiśniewski and Janosik (1974) with drawings by Jerzy Skarżyński (1924-2004).

In 1976, two comic magazines appeared on the market: Relax and Alpha. Relax published historical, fantasy, adventure and children's comics. Among the cartoonists were Janusz Christa, Tadeusz Baranowski (1945), Jerzy Wróblewski and Grzegorz Rosiński, who from 1978 published, among others, Thorgal to the script by Jean Van Hamme (1939).

The magazine was published in 1976-1981, 31 episodes were issued. A slightly different subject matter was taken up in Alpha. It was a magazine combining comics with science fiction and popular science subject matter. Between 1976 and 1985, 7 editions were published and Rosiński was the most important cartoonist publishing in it.

In the 1980s, there were album editions of, among others, formally innovative comic books by Tadeusz Baranowski, as well as Kajko i Kokosz (Kajko and kokosz) by Janusz Christa, Przygód Jonki, Jonka i Kleksa (The Adventures of Jonka, Jonek and Kleks) by Szarlota Pawel (1947-2018) and comic books by Jerzy Wróblewski. The print run reached several hundred thousand copies. In 1982, the monthly magazine Fantastyka began printing the Funky Koval series by the screenwriters Maciej Parowski (1946-2019) and Jacek Rodek (1956) and the graphic artist Bogusław Polch. It was a comic book about the adventures of a cosmic detective, with many references to modern times. It quickly gained huge popularity and to this day is considered to be one of the most important Polish series. Fantastyka also printed works by Grzegorz Rosiński and Zbigniew "Kas" Kasprzak (1955). Interest in comics was so big, that it led to the creation of the first Polish magazine for adult readers Komiks - Fantastyka (Comic - fantasy) in 1987. In 1990 it was transformed into Komiks (comic) and published until 1995. It published the most important European and Polish comic strips, among others, the mentioned Funky Koval and Yans by André-Paul Duchâteau (1925-2020) and Grzegorz Rosiński. The last six issues that were printed was Wiedźmin (The Witcher) series drawn by Bogusław Polch for the screenplay by Maciej Parowski based on the short stories by Andrzej Sapkowski (1948).

After the fall of communism, during the political, economic and social transformation, the Polish comic book was displaced by the previously absent reprints of American and Western European comic books. In the first half of the 1990s, the Polish comic book was also replaced by American and Western European comic books. Almost all the big publishing houses that were publishing the works of Polish authors went bankrupt. Polish comics went underground, where it developed in a strange niche. Artists deprived of places of publishing, started to present their work at exhibitions or reproduced them in self-published, technically imperfect zines. In the 1990s, comics flourished at the academies of fine arts and in art schools, among young artists who, unfettered by market demands and the need to adjust their aspirations to the rigors of commercial publishing, created comics that were artistically sublime and, more broadly, artistically. The most important illustrators and artistic personalities of the time were Krzysztof Gawronkiewicz from Warsaw (1969), Przemysław Truścinski from Łódź (1970) and Jerzy Ozga from Kielce (1968). They all met at the first Polish Convention of Comics Creators in the Zieliñski Palace in Kielce in February 1991. It was an event organized by two enthusiasts, Robert Łysak (1964) and the aforementioned Ozga. They invited to their city a group of young cartoonists and critics of the genre. The whole company in a relaxed atmosphere debated about the situation of comics in Poland. Representatives of the Łódź community, already associated in the "Contur" group, stood out from the rest of the group. They quickly expressed their desire to organize the second edition of the event in Łódź. This is how the event of decisive importance for the entire contemporary Polish comics scene was born - the National Convention of Comics Creators in Łódź. In 1999 it was renamed the National Comics Festival, in 2000 the International Comics Festival, and since 2009 it has functioned as the International Festival of Comics and Games. The second edition of the convention, the first in Łódź, took place in September 1991 in the Cultural Center in Łódź, which had just been opened after many years of renovation. The organizer was the above mentioned "Contur" group, comprising graduates of the Łódź High School of Fine Arts, and later students of the local Academy of Fine Arts.

One of the most important parts of the Festival in Łódź was the competition. Announced in 1991, a competition for "short form comics". For many years his output set trends in Polish comics and was a springboard in the careers of young cartoonists.The first edition at the still modest event was won by Robert Waga (1968). The second was Krzysztof Gawronkiewicz, the third Przemysław Truściński, the fourth Aleksandra Czubek-Spanowicz (1966), the fifth Sławomir Jezierski (1963)... These were artists presenting a variety of approaches to comics. In his 1969 novella, Gawronkiewicz adapted the memoirs of Sławomir Rogowski, using the classic comic book technique of pen drawing. Truściński shone with his experimental Inferno, a photo comic strip in which he himself appeared. Aleksandra Czubek - Spanowicz won the award for her painting Miasto nocą (City by Night) and Sławomir Jezierski won the award for O skarbie, co obcym się nie dał (About a Treasure Who Wouldn't Give Himself to Strangers), a fairy tale in which he perfectly combined black outline with watercolor color. Grand Prix winners at the Festival included Adrian Madej (1977), Tomasz Lew Leśniak (1977), Krzysztof Ostrowski (1976) and Jerzy Ozga. Łódź also awarded prizes to Olaf Ciszak (1977), Jakub Rebelka (1981), Benedykt Szneider (1982) and other great cartoonists. The competition jury included comics experts from Poland and abroad, such as Wojciech Birek (1961), Kája Saudek (1935-2015) and Jerzy Szyłak (1960).

Polish comics developed almost exclusively in the alternative circuit. After the collapse of Komiks (comic) magazine and a few attempts to publish national magazines, such as Fan, Awantura (Row), Super Boom!, Kelvin & Celsius, only low-circulation magazines remained on the market, e.g. Czas Komiksu and Komiks Forum, as well as zines, e.g. KKK, Mięso (Meat), some of which later turned into magazines, e.g. AQQ, Ziniol. Works of Polish comic artists could be seen in magazines related to widely understood fantasy and in the press. Occasionally, their albums appeared.

Groups, clubs and associations were thriving. Apart from the Łódź “Contur”, there were the Polish Comics Studio from Bydgoszcz and the Kraków Comics Club. Strong centers of comics creators and fans operated in Warsaw, Poznań, Tricity and Upper Silesia, among others.

In the year 2000 there was a comic book boom in Poland. A large group of publishers almost simultaneously bet on comics. The market was flooded with a huge number of titles, both by foreign and Polish authors. Polish comic artists were allowed the opportunity to present their comics to a wide audience. There appeared anthologies of works created in the 90's, new comic magazines, albums and series. Comics entered art schools and galleries. Serious academic publications devoted to this medium appeared. In the next few years the market normalized. Nowadays, readers in Poland have an opportunity to take advantage of the offer of many publishing houses which publish Polish and foreign comic books.

Co-financé par le Fonds de Promotion de la Culture du Ministère de la Culture, du Patrimoine National et du Sport.

Komentarze

Prześlij komentarz