Polish school of comics

Polish school of comics

Jerzy Szyłak

Jerzy Szyłak

Bohdan Butenko (1931-2019) made his debut in 1956. He mainly illustrated books, and the comics he made were made for younger readers. However, he was a man who introduced typical comic-book solutions to book illustrations: he put characters' statements (in speech bubbles or without them) or fragments of literary text into the frames of the pictures. He combined words with images in many ways: he enlarged the inscriptions and changed the typeface, making the letters expressive graphic elements of the composition of the pages of a book. He used exaggerations and simplifications, introduced into his drawings lines of movement and other symbols taken from comic books. His work was guided by the spirit of anarchy and contrariness, which forced him to take metaphorical phrases literally and pay attention to the comic elements hidden in the illustrated texts, even when it should not be done. Critics said that he made recipients read the pictures and watch the texts, which is, after all, a characteristic feature of comics. They also noticed the comic character of his illustrations. Butenko was the one who taught several generations of Poles to interact with comics. However, comic book lovers looked at him from a distance, seeing him mainly as the creator of stories for children, while the creators did not admit that he inspired them. It was not until Bartosz Minkiewicz (born in 1975) in an interview in 2012 that he realized that he owed Butenko a lot.

Butenko rarely said that he made comics (he preferred to use the term picture stories) and did not mention the comic character of his illustrations. This was because the comic was associated with the West and treated as an example of a degenerate capitalist culture. The effect of these propaganda measures was that comics were drawn and read, but efforts were made not to call them comics. Meanwhile, for the lovers of cartoon stories living in communist Poland, the native comics needed to look like those that were brought from time to time by someone from the West. They expected that there would be speech bubbles with quotations of characters, onomatopoeias inscribed in capital letters in the frames of frames, and drawings using expressive contours and vivid colors. Works, where the text was separated from the drawings and placed underneath them, were considered old-fashioned and made by someone who does not know what a comic should look like. It was similar to the works whose creators tried to introduce some innovations to the graphic layer of the stories they created. Meanwhile, among those who reached for the "old-fashioned" forms of cartoon stories were excellent graphic artists. In the years 1970-71, Szymon Kobyliński (1927-2002), an excellent graphic artist, illustrator, and set designer, drew a comic version of the popular TV series Four tank-men and a dog (Czterej pancerni i pies). However, this one was much less popular than Captain Kloss (Kapitan Kloss) drawn by Mieczysław Wiśniewski at the request of the Swedes, which was also an adaptation of a television series but drawn correctly at best.

In turn, in the pages of the magazine Alfa, two graphic artists with a completely different workshop presented their visions of the same story. Janusz Stanny (1932-2014) illustrated the first two parts of Tadeusz Lech's scenario In the Galactic Service (W służbie galaktycznej), and the illustrations for the next two were the work of Grzegorz Rosiński (born in 1941). Stanny made his first episode using painting techniques and creating works similar to his book illustrations, for which he received international awards from the mid-1960s. In the second, he used the poetics of pop art and decided to combine drawings with processed photographs. Rosiński presented realistic drawings and graphic solutions proving that at that time he was interested in the works of Jean-Claude Mèzierés. As you can guess, it was Rosiński's works that aroused the admiration of the readers.

In the 1970s, the circulation of the most popular comic books in Poland reached one million copies. Their creators (Grzegorz Rosiński, Jerzy Wróblewski, Janusz Christa, Henryk Jerzy Chmielewski, Bogusław Polch) are very popular to this day, and the reissues of their comics are eagerly bought. Their fame, however, was because they had no competition in the form of foreign comic book editions, and their works were partly an expression of those absent comics - known from descriptions in newspapers, a few copies brought by someone from abroad, and small fragments reprinted in magazines (most often from infringement of copyright). They created a kind of "comic-book everyday speech" pattern, against which other works were assessed, and those that did not follow this pattern were treated reluctantly.

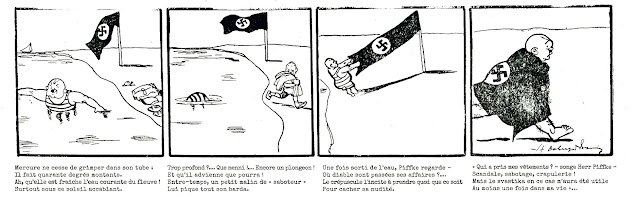

Among the artists who were badly received by a wide audience was also Jerzy Skarżyński (1924-2004), a painter, illustrator, and set designer, who collaborated in the theater, among others. with Konrad Swinarski, and in the cinema with Wojciech Jerzy Has. He became interested in comics in his childhood thanks to his father, who believed that thanks to them, his son would learn English. In the years 1972-1973 Janosik was released - a six-episode adaptation of a television series. Skarżyński referred in his comic book to the tradition of comics and Polish art and used original solutions resulting from his artistic experiences. He proposed to publish the comic in a large format, similar to the one in which American comics were published before the war, and additionally, he insisted that every second spread would be in black and white, which also referred to the tradition which was the result of savings (the printed sheet was colored with on one side only, which had this effect). The style of the drawings referred to the expressive line of Milton Caniff, used, however, by an artist who had already come across the works of Roy Lichtenstein and, like the American painter, redraws, highlights, and simplifies. Skarżyński's framing was thoroughly modern: the protagonists tried to escape from the frames of the frames, while the frames bent and took unexpected shapes, trying to prevent this from happening. In his later works, Skarżyński gave up frames altogether, filling comic book boards with open compositions, in which the sequence of representations was indicated by repeated representations of the same characters performing certain activities. He did not like comics in Poland, but in 1975 Skarżyński had an individual exhibition at the comic book festival in Lucka, and a year later he was also a guest there. In later years, he also traveled to Italy, less officially, and after returning from there, he wrote texts informing about the most interesting phenomena in comics in the world. He also started working with the Italian comic magazine Sgt Kirk, where he published several comics, of which only one was reprinted in Poland (and with a long delay).

When in 1988 the Swiss prepared a collective exhibition of Polish comics and asked Polish publishers for help, they put them in touch with the most popular, mainstream authors. They were Bogusław Polch, Tadeusz Baranowski, Zbigniew Kasprzak and Grzegorz Rosiński, who then lived and worked in Belgium, but he was the initiator of the Polish exhibition. The organizers, however, asked for Skarżyński (as well as Andrzej Mleczko), in a way correcting the Poles' perception of what is best in Polish comics. A side effect of this exhibition was that one of the editors of the monthly Fantasy (Fantastyka) - Maciej Parowski, who was in Sierre as a comic book writer for Funky Koval - became interested in Skarżyński's new comic works and presented them in the gallery in his magazine. The most important of these was the wordless comic book by P.E. (short for pitecantropus erectus). Parowski even planned to publish the comic in its entirety in Fantasy (Fantastyka). Ultimately, the publication did not take place, and in addition, some of the boards in the editorial office were lost forever.

At the turn of the sixties and seventies, authors of comic books and satirical drawings appeared in Poland, whose works related to the American underground with their style and subject matter. They were published in satirical magazines, where they presented short satirical stories, presenting Polish reality in a crooked mirror. Their promoter was the then editor-in-chief of the weekly High-heeled shoes (Szpilki), Krzysztof Teodor Toeplitz, an expert on comics, its promoter, and author of the first Polish book devoted to this artistic phenomenon. He wrote with admiration about underground comics - especially about the works of Robert Crumb - and successfully promoted the Polish version of such comics. Of course, Polish comics were censored and to a certain extent top-down, and their creators were not allowed to tackle uncomfortable topics. However, they were seen as truly bold and innovative in form. Their creators - Andrzej Mleczko (born in 1949), Andrzej Czeczot (1933-2012), Andrzej Krauze (born in 1947), Andrzej Dudziński (born in 1945) - did not perceive themselves as creators of comics and did not limit their work to creating them. Most of them graduated from academies of fine arts and at various times started cooperating with foreign magazines. In their comics, they made use of the experiences of various artists: comic book artists, satirists, and visual artists.

In Polish comics, three trends can be distinguished, which determine its specificity: mainstream, which is the most popular among recipients, and which consists in racing with a certain, quite idealized, image of Western comics. It gained its dominant position during the Polish People's Republic when no Western comic books were published in Poland. Its basis, however, was an excellent graphic workshop, as evidenced by the fact that some of these artists (Rosiński, Kasprzak, Polch) then (in the seventies) found employment in Western publishing houses. Today, their followers and followers have to fight foreign competition, which is better advertised and supported by the awareness that we are dealing with comics popular all over the world. For this reason, some of the cartoonists belonging to this group began to look for employment outside Poland and found them, and now their comics are published as reprints.

The underground trend, which in the People's Republic of Poland was top-down and limited, after the political transformation inspired many young cartoonists to use his experiences to present their thoughts, views, and frustrations. Its anti-aesthetic nature and the suggestion that the importance of the subject may pay for the imperfection of the form and the impression that in this case we are dealing with a personal statement and sincerely translated into works published in various zines published outside the official circulation often copied on photocopying without censorship (which was completely abolished in Poland at that time) and without the supervision of professional editors.

Large publishing houses in Poland continued to rely on proven cartoonists and were looking for new artists who could draw like them. However, it did not bring the expected results. In a country whose borders had been opened, works resembling Western comics were losing out to works imported from the West. But apart from large publishing houses, a new generation of artists was taking shape, who combined experiments with a form with underground poetics, talked about what hurts them and what they care about. For some of them, publishing in zines was a workshop on polishing their skills and led them to publish fully professional items. This was the path taken by Michał Śledziński (born in 1978), Rafał Skarżycki (born in 1977) and Tomasz Leśniak (born in 1977), Karol Kalinowski (born in 1982), brothers Bartosz and Tomasz (born in 1978), the Minkiewicz family, Mateusz Skutnik (born in 1976), Anna Krztoń (born in 1988), Marcin Podolec (born in 1991) and a number of other artists. They create stories in various poetics, fitting into the framework of various genres (from satire, through fantasy stories to autobiographical things). What connects their works is the spirit of anarchy and contrariness, which makes them look for unusual plot and graphic solutions, go beyond the framework of everyday comic speech, violate conventions and conventions. All this to say something with your voice.

Komentarze

Prześlij komentarz