A brief overview of the achievements of Polish comics experts

A brief overview of the achievements of Polish comics experts

Michał Traczyk

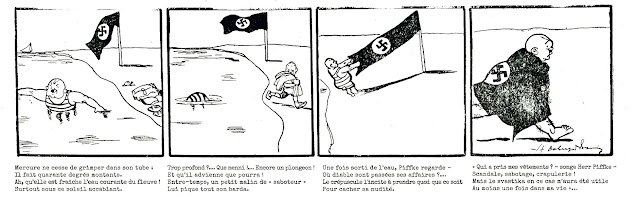

Before World War II, picture stories in Poland gained a lot of popularity among readers. They appeared mainly in the press. They were boosting its sales, so quite a lot of them appeared. Since comics were most often used for entertainment, their authors did not always treat this type of creativity as a serious occupation. Critics, if noticed, left no doubt about their artistic and cultural value. They focused more on the scale of the occurrence of these stories in the English-language press.

Critics' increased interest in comics appeared after World War II, not because of the artistic value of the genre, but in the context of political and ideological games. The Polish press blamed the comic book for the moral decline of the Americans and for bringing up children to crime. Picture stories, according to Polish journalists, were without exception cheesy and infantile, they were a source of illiteracy and racism, influencing young minds and making them addicted to the likeness of drugs.

The line of criticism adapted in the post-war period remained in the public consciousness for many years. The image of a comic book as a worthless medium of shallow and dangerous content could not be changed by rare, substantive analyzes to varying degrees, which were exceptions to the generally prevailing rule, such as the discussion by Aleksander Hertz, published in Forge (Kuźnica) in 1947, in which the Polish sociologist recognized comics as a variant of fairy tales referring to myths and values important for American society; A little history of comics (Mała historia komiksów) by Andrzej Banach (1964), containing not only a breakneck comparison of comic book types to literary genres (epics, drama, and lyricism) but also situating the beginnings of this genre in ancient Egypt; or articles by Janusz Dunin (1971, 1972), bringing a definition, discussion of genre features and history, reflection on the comic book popularity and its reception. Moreover, it is Dunin who makes the first attempt to reflect on the history and conditions of comic book presence in Poland. It is true that he cannot (or does not want) to refrain from evaluating the comic book openly in the tradition of literature of the highest caliber, but one gets the impression that this is because, in his opinion, Polish productions are not very successful.

The turn of the 1970s and 1980s brought a significant revival in the field of comic studies reflection. There are new texts that reveal a much greater than average awareness of comics. Sławomir Magala focuses on the works of Robert Crumb (as a representative of the American underground), calling them third-generation comics, and Andrzej Mleczko (according to the researcher, the Polish equivalent of Crumb). Sergiusz Sterna-Wachowiak Ryszard Przybylski proposes semiotic analyzes, Krzysztof Teodor Toeplitz publishes the first fragments of the book he is preparing, and the editors of Film in the world (Film na świecie) devote a whole number to comics and their film adaptations. The popular notebooks that were published at that time appeared in the circle of interest. Although analyzed from different perspectives, they evoked similar feelings in researchers and critics, describing them in terms of stereotype and primitive didacticism or as examples of propaganda graphomania.

The situation at that time meant that in 1984, in Fantasy (Fantastyka), Maciej Parowski, a columnist defending comics as art, provoked by critical voices of readers dissatisfied with the publication of comic books by Fantasy (Fantastyka), presented a bitter diagnosis of the comic book situation and the reflection devoted to it in Poland. At the same time, he expressed the hope that the comic book situation in Poland would change soon, after all, the book by K.T. Toeplitz.

The Art of Comics. An attempt to define a new artistic genre. (Sztuka komiksu. Próba definicji nowego gatunku artystycznego), Toeplitz's attempt to define a new artistic genre appeared a year later. This is the first and for over a decade the only book that for many years has shaped the awareness of Polish comic book researchers, providing them with what has been lacking in Polish reflection so far - focus on the language of comics, its aesthetic layer, at the expense of sociological analyzes. Toeplitz proposes an extensive definition of a comic book, looks at its various components: the construction of characters, space in comic narration, the role of text and sign, and reflects on the place of comics among other plays.

The 1990s was a difficult time for Polish comics. The rapid socio-economic changes that followed the fall of communism meant that suddenly it was possible to spend everything without restrictions and censorship, therefore the domestic market was flooded with foreign comics, while Polish albums disappeared for nearly a decade - publishing them happened after just unprofitable. The situation forced the authors to look for alternative solutions, the most durable of which turned out to be zines - low-circulation magazines prepared by artists themselves, presenting, apart from their work, also current journalism. The title that stood out from the crowd was the “AQQ” magazine founded in 1993 by Witold Tkaczyk and Łukasz Zandecki - which, after its zine beginnings, became professional. It was the only press title devoted to comic books that survived almost until the middle of the first decade of the 21st century, and the only journalistic and journalistic one to such an extent - it was a kind of chronicle of Polish comics, offering extensive reports from events, interviews with comic book people, reviews of new products, noting all, even the smallest information about the broadly understood comic book culture, and supplement it with problem articles. However, the chronicler's flair and keeping the finger on the pulse, which constituted the strength of “AQQ” in the 1990s, in the next decade turned out to be insufficient in the confrontation with new technologies. The role of the source of current information has been taken over by the increasingly popular Internet. It can be said that the closure of “AQQ” in 2004 symbolically sealed the separation of two spheres: journalistic with current, up-to-date information, which was permanently transferred to the web, and scientific, which remained in the traditional, journal and book circulation. In the same year, the leading online information portal Avenue of Comics (Aleja Komiksu) and the printed magazine Comic Booklets (Zeszyty Komiksowe) were created.

The beginning of the 1990s was also a time of increased, or rather increasing, research activity. Adam Rusek, Jerzy Szyłak and Wojciech Birek - today undisputed authorities in the Polish comic studies community - publish their journalistic and scientific texts. They do it using traditional channels available to scientists (specialist press, collective books, most often post-conference books), but also the pages of almost all environmental titles, both unofficial (zines) and those trying to function (the vast majority with poor results) on market principles.

Adam Rusek undertook an extremely difficult task - to reconstruct the history of Polish comics. Known previously only in a rudimentary way, from a few brief descriptions or lists, based on memories and collections. Rusek based his research on tedious and time-consuming press queries, counted in hundreds of hours and tens of thousands of pages, rightly assuming that it is in the pages of Polish periodicals that most of the answers to his questions about the tradition of Polish picture stories can be found.

The titanic work has resulted in fundamental studies, the titles of which already reveal Rusek's research assumptions - he is interested in stories presented in a series of pictures, occurring cyclically (thus he omits one-off projects that do not have a continuation), while the characteristic of this researcher is the non-differentiation of picture stories into protocols or paracomixes and "proper" comics (with text placed within the pictures), which - on the one hand - allows him to show genre complexity, taking into account the specificity of Polish "picture novels" (in most picture cycles with text, often rhymed, placed under the drawings), with the second - the historical continuity of national picture stories, beginning with the first cycles of Artur Bartels and Franciszek Kostrzewski from the 19th century.

Nobody has done so much for Polish comics and research on its history. Rusek not only checked and verified the myths and images functioning in the community, restored many names and titles (by providing examples of them or publishing them in full - he is also the editor of the so far four-volume series Old Polish Comics (Dawny komiks polski), but he discovered at least twice as many authors and works that no one had ever reached before him, working on it all: deciphering pseudonyms, establishing facts from the biographies of authors, tracing references, adaptations and borrowings; and, above all, making it aware of the real scale of comic book functioning in Poland before and after World War II (supported by extensive bibliographic compilations in all studies). In addition, the comic book is a living phenomenon for Rusek, rooted in reality, deeply embedded in socio-political contexts (reacting to current changes and often being a victim of these changes).

Jerzy Szyłak is undoubtedly the most prolific comic book researcher in Poland. Although he prefers to present himself as a film expert, he has written far more books about comics than about films. He began writing, then these were journalistic texts, in the mid-1980s, but the beginnings of his scientific activity fell in the next decade (his first book was published in 1996), and he established his position at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, especially by publishing the trilogy: Comics: a world redrawn (Komiks: świat przerysowany) (1998), Comics in the iconic culture of the 20th century (Komiks w kulturze ikonicznej XX wieku) (1999) and Poetics of comics. The iconic and linguistic layer (Poetyka komiksu. Warstwa ikoniczna i językowa) (2000), the reading of which from then on will become a necessary condition in the process of shaping the awareness of each new adept of Polish comic studies. These are books that provide readers with a comprehensively thought-out image: from scratch, the components from which pictorial stories are constructed, through the genre specificity of the comic, to placing it in the context of other genres, indicating its place and role in the history of culture.

The above-mentioned books are complemented and, at the same time, a confirmation of Szyłak's dominant position in Polish comic book research from the very beginning, other titles are showing the main areas of his interests: the dark aspects of the sexual sphere related to physical and psychological violence, as well as the relationship between the comic book and the film. Szyłak also wrote the first popular science book addressed to a wider circle of readers, providing a position popularizing picture stories (his other texts are specialist in nature). To this day, it remains one of only three publications of this type in Poland.

Szyłak's position did not mean, however, that he accepted his proposals indisputably, his expressive and well-argued theses provoked dialogue, but also did not facilitate polemics. Being a literary scholar by education, pointing to the important role of representatives of the science of literature in the study of comic book art and formulating theses about literary relations between comics, Szyłak, and literary scholars in general, were accused of appropriating comics and impoverishing reflection by limiting themselves to one narrow perspective, making it impossible to according to critics, dealing with comics competently. The conflict, which was famous for many years in the comic book community, had been growing for over a decade, fueled primarily by Krzysztof Skrzypczyk, who called for the creation of a separate field of science - comicsology, the organizer of comic book symposia, held in 2001-2012 at the International Festival of Comics and Games in Łódź (these meetings resulted in anthologies presenting the presented papers). Szyłak, who initially tried to discuss, quite quickly adopted a waiting position (apart from the articles, only the reissues of two of his books and a collection of articles previously published on the web, as well as undeveloped ideas for subsequent books were published), to finally take the floor with the volume Comic book in the claws of mediocrity. dissertations and sketches (Komiks w szponach miernoty. Rozprawy i szkice) (2013), devoted to the spoiling of science (it deals with Skrzypczyk's comics and the concept of story art by Jakub Woynarowski).

In the following years, Szyłak devoted to exploring other topics, being one of the initiators and authors of the lexicon of graphic novels, writing a book on the boundaries of the graphic novel and expanding the circle of his interests with picture books (for example, he is the editor and co-author of a three-part lexicon of picture books).

Wojciech Birek is a researcher who did not get a book for a very long time. This does not change the fact that the researcher has been actively working for comics since the end of the 1980s, publishing, creating, translating not only comics - his translation achievements include (next to about a thousand comics), among others Grzegorz Rosiński. Monography (Grzegorz Rosiński. Monografia) by Patrick Gaumer and Piotr Rosiński (2015) and Thierry Groensteen's The System of Comics (System komiksu), still waiting to be printed. Most of Birek's scientific texts appeared in collective works and specialist journals, which meant that this part of his activity remained little known in the comic book environment for a long time. The situation changed in 2014 with the publication of the book From comic book theory and practice. Proposals and observations (Z teorii i praktyki komiksu. Propozycje I obserwacje), gathering a large part of the scattered articles. However, on the magnum opus of Birek, Henryk Sienkiewicz in pictures. Drawings by Henryk Sienkiewicz and pictorial adaptations of his novels (Henryk Sienkiewicz w obrazkach. Rysunki Henryka Sienkiewicza i obrazkowe adaptacje jego powieści), which is the culmination of many years of research and research conducted around the world, we had to wait until 2018.

Recent years have been a time of increasing activity of other, younger researchers, who develop new areas or contribute to the topics already undertaken. Books about historical comics, superheroes, mythical (and not only) inspirations, as well as cognitive genre analyzes have appeared. During this period, collective works were published relatively regularly, being the aftermath of conferences or lectures organized in Poznań. The activity of authors without the scientific background of those responsible, inter alia, for publications devoted to the Świętokrzyskie comics and the beginnings of Polish graphic stories, Jerzy Wróblewski and the comic book of the Polish People's Republic, or introducing the series about Captain Wildcat (Kapitan Żbik) and the magazine Relax. Most of them are books related to nostalgic thinking about authors and titles from before the political transformation.

From time to time, thematic issues of specialist magazines appear: pedagogical, literary, cultural, comic books, but one magazine was devoted entirely to the Ninth Art. Comic Booklet (Zeszyty Komiksowe), founded in 2004, offers monographic issues from the very beginning. It is the only journal of this kind in Poland, in which you can find texts not only (almost all) native researchers, but also translations from several languages.

Apart from strictly scientific or commercial publishing houses, with individual titles devoted to picture stories, books about comics were also published by publishers publishing comics daily: The Central (Centrala) (2), Timof comics (3), including the translation of the book Comics versus art (Komiks kontra sztuka) by Bart Beaty), Kurc (4). Since 2015, the leader in publishing this type of literature has been the Institute of Popular Culture (7), also responsible for Comic Booklets (Zeszyty Komiksowe) (since 2015, 14 issues and reprints of 6 older ones, the magazine is published together with the University Library in Poznań).

In this context, the organizational activity of various institutions is also significant, often combined with the implementation of publishing plans, such as in the case of the already mentioned Institute of Popular Culture (a publishing project of the Popular Culture Institute Foundation). An initiative worth noting is the exhibition activity conducted by the Bureau of Art Exhibitions in Jelenia Góra. Exhibitions, whether monographic or cross-sectional, for which the curator Piotr Machłajewski is responsible, are accompanied by catalogs, often exceeding, both in terms of volume and approach to the subject, the standards of typical catalogs. They are rather album monographs or books that can hardly be called catalogs. The bilingual publication Now a Comic! (Teraz komiks!), Accompanying the exhibition organized at the National Museum in Krakow in 2018, has a similar character, combining the album's momentum with an extensive study of the topic.

It is also worth mentioning the books presenting Polish comic book achievements abroad: Histoire de la bande desinée polonaise (2020) - a history of Polish comics prepared for the French market, as well as two available in German: Comic in Polen - Polen im Comic (2016) and Handbuch polnische Comickulturen nach 1989 (2021).

A comparison of the present state of comic studies reflection in Poland with that of 30 years ago leaves no doubt that we were dealing with a huge leap. Due to the new socio-political reality and new cognitive possibilities, the awareness of Poles is systematically changing, though probably not as quickly as one might wish for, and thus more and more people recognize the value and variety of comics. This translates into both the number of young researchers willing to take up comics topics and the number of publications. And while there is still a lot of work to be done, today it seems that making up for years of neglect in this area is only a matter of time.

Michał Traczyk

Before World War II, picture stories in Poland gained a lot of popularity among readers. They appeared mainly in the press. They were boosting its sales, so quite a lot of them appeared. Since comics were most often used for entertainment, their authors did not always treat this type of creativity as a serious occupation. Critics, if noticed, left no doubt about their artistic and cultural value. They focused more on the scale of the occurrence of these stories in the English-language press.

Critics' increased interest in comics appeared after World War II, not because of the artistic value of the genre, but in the context of political and ideological games. The Polish press blamed the comic book for the moral decline of the Americans and for bringing up children to crime. Picture stories, according to Polish journalists, were without exception cheesy and infantile, they were a source of illiteracy and racism, influencing young minds and making them addicted to the likeness of drugs.

The line of criticism adapted in the post-war period remained in the public consciousness for many years. The image of a comic book as a worthless medium of shallow and dangerous content could not be changed by rare, substantive analyzes to varying degrees, which were exceptions to the generally prevailing rule, such as the discussion by Aleksander Hertz, published in Forge (Kuźnica) in 1947, in which the Polish sociologist recognized comics as a variant of fairy tales referring to myths and values important for American society; A little history of comics (Mała historia komiksów) by Andrzej Banach (1964), containing not only a breakneck comparison of comic book types to literary genres (epics, drama, and lyricism) but also situating the beginnings of this genre in ancient Egypt; or articles by Janusz Dunin (1971, 1972), bringing a definition, discussion of genre features and history, reflection on the comic book popularity and its reception. Moreover, it is Dunin who makes the first attempt to reflect on the history and conditions of comic book presence in Poland. It is true that he cannot (or does not want) to refrain from evaluating the comic book openly in the tradition of literature of the highest caliber, but one gets the impression that this is because, in his opinion, Polish productions are not very successful.

The turn of the 1970s and 1980s brought a significant revival in the field of comic studies reflection. There are new texts that reveal a much greater than average awareness of comics. Sławomir Magala focuses on the works of Robert Crumb (as a representative of the American underground), calling them third-generation comics, and Andrzej Mleczko (according to the researcher, the Polish equivalent of Crumb). Sergiusz Sterna-Wachowiak Ryszard Przybylski proposes semiotic analyzes, Krzysztof Teodor Toeplitz publishes the first fragments of the book he is preparing, and the editors of Film in the world (Film na świecie) devote a whole number to comics and their film adaptations. The popular notebooks that were published at that time appeared in the circle of interest. Although analyzed from different perspectives, they evoked similar feelings in researchers and critics, describing them in terms of stereotype and primitive didacticism or as examples of propaganda graphomania.

The situation at that time meant that in 1984, in Fantasy (Fantastyka), Maciej Parowski, a columnist defending comics as art, provoked by critical voices of readers dissatisfied with the publication of comic books by Fantasy (Fantastyka), presented a bitter diagnosis of the comic book situation and the reflection devoted to it in Poland. At the same time, he expressed the hope that the comic book situation in Poland would change soon, after all, the book by K.T. Toeplitz.

The Art of Comics. An attempt to define a new artistic genre. (Sztuka komiksu. Próba definicji nowego gatunku artystycznego), Toeplitz's attempt to define a new artistic genre appeared a year later. This is the first and for over a decade the only book that for many years has shaped the awareness of Polish comic book researchers, providing them with what has been lacking in Polish reflection so far - focus on the language of comics, its aesthetic layer, at the expense of sociological analyzes. Toeplitz proposes an extensive definition of a comic book, looks at its various components: the construction of characters, space in comic narration, the role of text and sign, and reflects on the place of comics among other plays.

The 1990s was a difficult time for Polish comics. The rapid socio-economic changes that followed the fall of communism meant that suddenly it was possible to spend everything without restrictions and censorship, therefore the domestic market was flooded with foreign comics, while Polish albums disappeared for nearly a decade - publishing them happened after just unprofitable. The situation forced the authors to look for alternative solutions, the most durable of which turned out to be zines - low-circulation magazines prepared by artists themselves, presenting, apart from their work, also current journalism. The title that stood out from the crowd was the “AQQ” magazine founded in 1993 by Witold Tkaczyk and Łukasz Zandecki - which, after its zine beginnings, became professional. It was the only press title devoted to comic books that survived almost until the middle of the first decade of the 21st century, and the only journalistic and journalistic one to such an extent - it was a kind of chronicle of Polish comics, offering extensive reports from events, interviews with comic book people, reviews of new products, noting all, even the smallest information about the broadly understood comic book culture, and supplement it with problem articles. However, the chronicler's flair and keeping the finger on the pulse, which constituted the strength of “AQQ” in the 1990s, in the next decade turned out to be insufficient in the confrontation with new technologies. The role of the source of current information has been taken over by the increasingly popular Internet. It can be said that the closure of “AQQ” in 2004 symbolically sealed the separation of two spheres: journalistic with current, up-to-date information, which was permanently transferred to the web, and scientific, which remained in the traditional, journal and book circulation. In the same year, the leading online information portal Avenue of Comics (Aleja Komiksu) and the printed magazine Comic Booklets (Zeszyty Komiksowe) were created.

The beginning of the 1990s was also a time of increased, or rather increasing, research activity. Adam Rusek, Jerzy Szyłak and Wojciech Birek - today undisputed authorities in the Polish comic studies community - publish their journalistic and scientific texts. They do it using traditional channels available to scientists (specialist press, collective books, most often post-conference books), but also the pages of almost all environmental titles, both unofficial (zines) and those trying to function (the vast majority with poor results) on market principles.

Adam Rusek undertook an extremely difficult task - to reconstruct the history of Polish comics. Known previously only in a rudimentary way, from a few brief descriptions or lists, based on memories and collections. Rusek based his research on tedious and time-consuming press queries, counted in hundreds of hours and tens of thousands of pages, rightly assuming that it is in the pages of Polish periodicals that most of the answers to his questions about the tradition of Polish picture stories can be found.

The titanic work has resulted in fundamental studies, the titles of which already reveal Rusek's research assumptions - he is interested in stories presented in a series of pictures, occurring cyclically (thus he omits one-off projects that do not have a continuation), while the characteristic of this researcher is the non-differentiation of picture stories into protocols or paracomixes and "proper" comics (with text placed within the pictures), which - on the one hand - allows him to show genre complexity, taking into account the specificity of Polish "picture novels" (in most picture cycles with text, often rhymed, placed under the drawings), with the second - the historical continuity of national picture stories, beginning with the first cycles of Artur Bartels and Franciszek Kostrzewski from the 19th century.

Nobody has done so much for Polish comics and research on its history. Rusek not only checked and verified the myths and images functioning in the community, restored many names and titles (by providing examples of them or publishing them in full - he is also the editor of the so far four-volume series Old Polish Comics (Dawny komiks polski), but he discovered at least twice as many authors and works that no one had ever reached before him, working on it all: deciphering pseudonyms, establishing facts from the biographies of authors, tracing references, adaptations and borrowings; and, above all, making it aware of the real scale of comic book functioning in Poland before and after World War II (supported by extensive bibliographic compilations in all studies). In addition, the comic book is a living phenomenon for Rusek, rooted in reality, deeply embedded in socio-political contexts (reacting to current changes and often being a victim of these changes).

Jerzy Szyłak is undoubtedly the most prolific comic book researcher in Poland. Although he prefers to present himself as a film expert, he has written far more books about comics than about films. He began writing, then these were journalistic texts, in the mid-1980s, but the beginnings of his scientific activity fell in the next decade (his first book was published in 1996), and he established his position at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, especially by publishing the trilogy: Comics: a world redrawn (Komiks: świat przerysowany) (1998), Comics in the iconic culture of the 20th century (Komiks w kulturze ikonicznej XX wieku) (1999) and Poetics of comics. The iconic and linguistic layer (Poetyka komiksu. Warstwa ikoniczna i językowa) (2000), the reading of which from then on will become a necessary condition in the process of shaping the awareness of each new adept of Polish comic studies. These are books that provide readers with a comprehensively thought-out image: from scratch, the components from which pictorial stories are constructed, through the genre specificity of the comic, to placing it in the context of other genres, indicating its place and role in the history of culture.

The above-mentioned books are complemented and, at the same time, a confirmation of Szyłak's dominant position in Polish comic book research from the very beginning, other titles are showing the main areas of his interests: the dark aspects of the sexual sphere related to physical and psychological violence, as well as the relationship between the comic book and the film. Szyłak also wrote the first popular science book addressed to a wider circle of readers, providing a position popularizing picture stories (his other texts are specialist in nature). To this day, it remains one of only three publications of this type in Poland.

Szyłak's position did not mean, however, that he accepted his proposals indisputably, his expressive and well-argued theses provoked dialogue, but also did not facilitate polemics. Being a literary scholar by education, pointing to the important role of representatives of the science of literature in the study of comic book art and formulating theses about literary relations between comics, Szyłak, and literary scholars in general, were accused of appropriating comics and impoverishing reflection by limiting themselves to one narrow perspective, making it impossible to according to critics, dealing with comics competently. The conflict, which was famous for many years in the comic book community, had been growing for over a decade, fueled primarily by Krzysztof Skrzypczyk, who called for the creation of a separate field of science - comicsology, the organizer of comic book symposia, held in 2001-2012 at the International Festival of Comics and Games in Łódź (these meetings resulted in anthologies presenting the presented papers). Szyłak, who initially tried to discuss, quite quickly adopted a waiting position (apart from the articles, only the reissues of two of his books and a collection of articles previously published on the web, as well as undeveloped ideas for subsequent books were published), to finally take the floor with the volume Comic book in the claws of mediocrity. dissertations and sketches (Komiks w szponach miernoty. Rozprawy i szkice) (2013), devoted to the spoiling of science (it deals with Skrzypczyk's comics and the concept of story art by Jakub Woynarowski).

In the following years, Szyłak devoted to exploring other topics, being one of the initiators and authors of the lexicon of graphic novels, writing a book on the boundaries of the graphic novel and expanding the circle of his interests with picture books (for example, he is the editor and co-author of a three-part lexicon of picture books).

Wojciech Birek is a researcher who did not get a book for a very long time. This does not change the fact that the researcher has been actively working for comics since the end of the 1980s, publishing, creating, translating not only comics - his translation achievements include (next to about a thousand comics), among others Grzegorz Rosiński. Monography (Grzegorz Rosiński. Monografia) by Patrick Gaumer and Piotr Rosiński (2015) and Thierry Groensteen's The System of Comics (System komiksu), still waiting to be printed. Most of Birek's scientific texts appeared in collective works and specialist journals, which meant that this part of his activity remained little known in the comic book environment for a long time. The situation changed in 2014 with the publication of the book From comic book theory and practice. Proposals and observations (Z teorii i praktyki komiksu. Propozycje I obserwacje), gathering a large part of the scattered articles. However, on the magnum opus of Birek, Henryk Sienkiewicz in pictures. Drawings by Henryk Sienkiewicz and pictorial adaptations of his novels (Henryk Sienkiewicz w obrazkach. Rysunki Henryka Sienkiewicza i obrazkowe adaptacje jego powieści), which is the culmination of many years of research and research conducted around the world, we had to wait until 2018.

Recent years have been a time of increasing activity of other, younger researchers, who develop new areas or contribute to the topics already undertaken. Books about historical comics, superheroes, mythical (and not only) inspirations, as well as cognitive genre analyzes have appeared. During this period, collective works were published relatively regularly, being the aftermath of conferences or lectures organized in Poznań. The activity of authors without the scientific background of those responsible, inter alia, for publications devoted to the Świętokrzyskie comics and the beginnings of Polish graphic stories, Jerzy Wróblewski and the comic book of the Polish People's Republic, or introducing the series about Captain Wildcat (Kapitan Żbik) and the magazine Relax. Most of them are books related to nostalgic thinking about authors and titles from before the political transformation.

From time to time, thematic issues of specialist magazines appear: pedagogical, literary, cultural, comic books, but one magazine was devoted entirely to the Ninth Art. Comic Booklet (Zeszyty Komiksowe), founded in 2004, offers monographic issues from the very beginning. It is the only journal of this kind in Poland, in which you can find texts not only (almost all) native researchers, but also translations from several languages.

Apart from strictly scientific or commercial publishing houses, with individual titles devoted to picture stories, books about comics were also published by publishers publishing comics daily: The Central (Centrala) (2), Timof comics (3), including the translation of the book Comics versus art (Komiks kontra sztuka) by Bart Beaty), Kurc (4). Since 2015, the leader in publishing this type of literature has been the Institute of Popular Culture (7), also responsible for Comic Booklets (Zeszyty Komiksowe) (since 2015, 14 issues and reprints of 6 older ones, the magazine is published together with the University Library in Poznań).

In this context, the organizational activity of various institutions is also significant, often combined with the implementation of publishing plans, such as in the case of the already mentioned Institute of Popular Culture (a publishing project of the Popular Culture Institute Foundation). An initiative worth noting is the exhibition activity conducted by the Bureau of Art Exhibitions in Jelenia Góra. Exhibitions, whether monographic or cross-sectional, for which the curator Piotr Machłajewski is responsible, are accompanied by catalogs, often exceeding, both in terms of volume and approach to the subject, the standards of typical catalogs. They are rather album monographs or books that can hardly be called catalogs. The bilingual publication Now a Comic! (Teraz komiks!), Accompanying the exhibition organized at the National Museum in Krakow in 2018, has a similar character, combining the album's momentum with an extensive study of the topic.

It is also worth mentioning the books presenting Polish comic book achievements abroad: Histoire de la bande desinée polonaise (2020) - a history of Polish comics prepared for the French market, as well as two available in German: Comic in Polen - Polen im Comic (2016) and Handbuch polnische Comickulturen nach 1989 (2021).

A comparison of the present state of comic studies reflection in Poland with that of 30 years ago leaves no doubt that we were dealing with a huge leap. Due to the new socio-political reality and new cognitive possibilities, the awareness of Poles is systematically changing, though probably not as quickly as one might wish for, and thus more and more people recognize the value and variety of comics. This translates into both the number of young researchers willing to take up comics topics and the number of publications. And while there is still a lot of work to be done, today it seems that making up for years of neglect in this area is only a matter of time.

Co-financé par le Fonds de Promotion de la Culture du Ministère de la Culture, du Patrimoine National et du Sport.

Komentarze

Prześlij komentarz